Straight from the Horse’s Mouth

How Balance, Condition, and Performance Can Start With the Teeth

Click here to read the full article in our digital edition.

By Kristen Spinning

There are typical signs that indicate there could be a problem with your horse’s teeth: loss of feed while eating, difficulty chewing, and getting plenty of groceries yet losing body condition. A growing number of vets and equine dentists are certain there are other, seemingly unrelated symptoms that can be traced right back to the horse’s mouth. They contend that dropping a lead, refusing a fence, uneven flexion, and just plain being cranky can all be attributed to dental pathology. It makes logical sense; if I had a toothache, I wouldn’t want to jump either. But the logic behind this view of equine dentistry goes beyond the pain of a simple toothache. At its core is the notion that imbalance in the mouth leads to imbalance elsewhere, which can affect health, performance, and overall well-being.

There are typical signs that indicate there could be a problem with your horse’s teeth: loss of feed while eating, difficulty chewing, and getting plenty of groceries yet losing body condition. A growing number of vets and equine dentists are certain there are other, seemingly unrelated symptoms that can be traced right back to the horse’s mouth. They contend that dropping a lead, refusing a fence, uneven flexion, and just plain being cranky can all be attributed to dental pathology. It makes logical sense; if I had a toothache, I wouldn’t want to jump either. But the logic behind this view of equine dentistry goes beyond the pain of a simple toothache. At its core is the notion that imbalance in the mouth leads to imbalance elsewhere, which can affect health, performance, and overall well-being.

To understand the biodynamic web that connects hoof to mouth, we first need a primer on how horses eat. For a straightforward approach to that anatomical journey, I recieved insight from Barbara Truex, DVM, who is a holistic veterinarian from Tucson, Arizona, and also serves as president of the Arizona Quarter Horse Association.

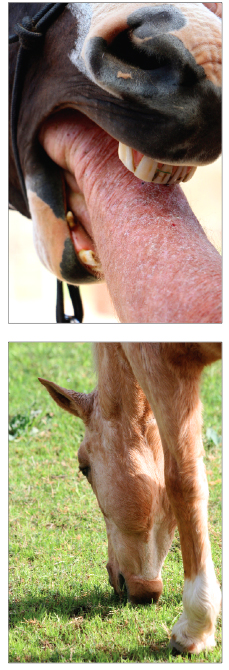

Step One: Food goes in. That’s the easy part. The incisors, or front teeth, are designed to bite off forage. The tongue moves it back to the cheek teeth, i.e. pre-molars and molars. Step Two: Chew. Here is where things can get complicated. A horse has seven major muscles of mastication, designed to work the mandible, or jaw, in a horizontal fashion. That is, cheek teeth don’t just clamp down on the food. They come together and slip sideways in a figure eight motion to grind food. The ground forage is mixed with saliva and softens, beginning the digestive process before even hitting the stomach. The slippage between the occlusal surfaces of the teeth (better known as the parts that touch) is influenced by the table angle, or natural slope of the molars. That table angle can be different based on breed, width of the head, length of the jaw, and age.

In theory, the horse’s teeth are a self-maintaining system. Wear from chewing forage is counter-balanced with the slow, continual eruption of teeth. By age five, most horses have their permanent teeth, and those teeth are fully grown. A young adult horse will have teeth that are 3.5 to 4 inches long, but the majority of the crown remains below the gum line in the dental socket. As the horse ages, periodontal ligaments push the tooth up through the gum line at about 1/8 inch per year. In a perfect horse world, that rate matches with the natural grinding down of the tooth surface.

Unfortunately, that perfect system doesn’t always stay in balance. Phil Ratliff, a longtime equine dentist, who works closely with veterinarians, describes some of the causes for uneven wear. “Environmental stress is anything other than eating,” he says. “It’s a major factor in how dysfunctional pathology in the mouth can develop. These stresses can include types of feed, saddle fit, an injury, rider imbalance, training regimen, confinement, and even the vibrational forces of trailering long distances on the highway.” Small, even minute changes in the natural, self-balancing cycle of wear and eruption set off a complex sequence of cause and effect, which ultimately results in hooks, ramps, and sharp enamel points. But our horse’s health and performance may be affected long before we see the obvious, abnormal dental signs.

Ratliff and Dr. Truex contend that small impediments in the chewing motion cause muscular changes as the horse tries to adapt. “Horses want to be in balance. Homeostasis,” Dr. Truex says. “The body is constantly striving for neutral position.” The horse also needs to eat, so if the side-to-side grinding isn’t working, they change chewing motion. Dr. Truex explains further, “When incisors get too long, or enamel points are in the way, even by a small amount, horses start biting up and down, chomping their food.” Though they can mash it up enough to swallow, this action is not efficient, and it disrupts the rest of the digestive process. The vital nutrients in the food are not properly absorbed when the grain, hay, grass or pellets, is not properly ground before reaching the stomach. This can result in poor body condition, changes in hair coat, changes in the hoof wall, and a host of other nutrition-related problems.

The effects of improper chewing may go beyond digestion, however. This integrative approach to equine dentistry speculates that biodynamic changes in the muscles of mastication can set off a chain reaction as the body tries to regain homeostasis. Ratliff explains that everything within a horse is designed to work in a specific and connected order. Balance, proprioception, and locomotion all start with the head. When something is out of alignment in the head, it can affect all those other systems. If muscles in the head are asymmetrical, because the horse has a problem chewing, then it can cause other muscular changes downstream. The imbalance can translate and amplify all the way through the body, causing pain. Pain in the body can then work back through the system and exacerbate the original chewing problem. A cycle of irregular dental pathology develops. In short, Ratliff contends the teeth have to line up correctly to keep the entire horse working properly. “It’s like those enormous domino setups they do in a gymnasium,” Ratliff says. “If you don’t hit the first one right, you leave some standing in the end.”

If so much is going wrong because of a little tooth point, why don’t we have obvious signs? Dr. Truex explains, “Horses are prey animals, and, as such, they will always try to project an image of perfect health. When they are not in balance, they are constantly compensating.” It takes a lot of energy to compensate, and that wears on performance. Also, as muscles try to adjust, they put more stress on the body, causing pain. That pain may present as irritability, difficulty turning to one side over another, dropping a hindquarter, or dragging a toe. As riders, we might think those ragged right hand circles are from a sore neck, but rarely would we think to look at the canines as the source of the neck pain.

The pain and stress of compensating for imbalances may result in behavior issues as well. “Sometimes, we’ll see a horse that is spooky or flighty,” Ratliff says. “They are not confident in themselves or their ability.” Upon examination, he has often found that a spooky horse doesn’t have proper range of motion in their jaw due to abnormal dental pathology. “Often, it takes only a millimeter or two of correction. The horse is able to get back in balance, and their other problems resolve.” Ratliff is adamant about making minimal adjustments, because the last thing he wants to do is create a new problem by removing too much tooth surface.

The pain and stress of compensating for imbalances may result in behavior issues as well. “Sometimes, we’ll see a horse that is spooky or flighty,” Ratliff says. “They are not confident in themselves or their ability.” Upon examination, he has often found that a spooky horse doesn’t have proper range of motion in their jaw due to abnormal dental pathology. “Often, it takes only a millimeter or two of correction. The horse is able to get back in balance, and their other problems resolve.” Ratliff is adamant about making minimal adjustments, because the last thing he wants to do is create a new problem by removing too much tooth surface.

In cases of pronounced or longstanding dental problems, the physical correlations can be quite dramatic. “We see some distinctive body patterns in horses with dental issues,” Dr. Truex says. “Those horses are often hollowed out behind the shoulders and hips.” She can’t definitively state whether it’s a result of poor nutrition due to the inefficiency of eating or if it’s the result of balance issues, which cause muscles to atrophy in one area and develop elsewhere. One of the challenges to the whole body approach to equine dentistry is that there appears to be many causal relationships, but no empirical evidence has been established. The specific biomechanical link between a horse’s teeth and other systems hasn’t been researched in a university setting.

Dental practitioners, vets, trainers, and horse owners only have anecdotal and observational evidence of how correcting one can improve the other. Dr. Truex, who rides reining and cow horses, says, “The data suggests that it’s all related. We can see the change in performance after correcting dental issues. But until somebody studies it, we can’t be certain what exactly is going on.” Observation seems to be enough for many top performance horse trainers. Competitors from cutting to jumping to western pleasure see dentistry as an invaluable tool to maximize their horses’ health and well-being.

In order to get a glimpse of what may be changing inside the horse, some practitioners use thermal imaging. Ratliff uses before and after thermal pictures to document changes. “We don’t use thermal imaging to diagnose anything. The pictures simply show us patterns of heat.” Often, heat is an indication of inflammation. In a horse with abnormal dental pathology, there are signs of concentrated heat. Some of those muscles of mastication will show very hot. Upon physical examination, those same muscles will feel hard, indicating a stress. After dental adjustments, the images show a dramatic change in the heat patterns, and the muscles become relaxed.

A horse’s return to balance after resolving dental problems can be seen within a few minutes or it may take a couple weeks. Sometimes, other holistic modalities are beneficial for restoring the muscles and body to symmetry. These could include massage, myofascial release, acupuncture, or chiropractic care. As with any health care regime, it is important to be knowledgeable and thoughtful in choosing a dental practitioner or vet who performs dental work. Dr. Truex cautions, “You don’t have to go along with what your barn manager or trainer says. Just because the dentist is in the barn that day, it doesn’t mean your horse has to have dental work.” She suggests horse owners talk to other people to see what kind of results they’ve had with their equine dentists.

Ratliff recommends regular dental exams and adjustments are necessary to maintain optimal occlusion but urges owners to be wary of having teeth floated just for the sake of floating. “If it won’t help him to eat better or improve performance, then he doesn’t need it,” he cautions. He believes in viewing a horse as a set of integrated systems, and that horses benefit when vets, farriers, and dentists understand how all the systems work together. The old phrase, “straight from the horse’s mouth,” may take on a whole new meaning once horse owners look at how important dentistry can be to overall health and well-being.