Osteoarthritis in Horses

By Brian S. Burks, DVM

Diplomate, ABVP

Board Certified in Equine Practice

Arthritis is joint inflammation. Breaking its roots, arthro- refers to the joint, while -itis means inflammation. Horses can get different types of arthritis, including osteoarthritis (osteo- refers to bone) and septic arthritis. Osteo arthritis is a chronic, progressive, painful degeneration of the cartilage at the ends of long bones, along with the underlying bone and soft tissues.

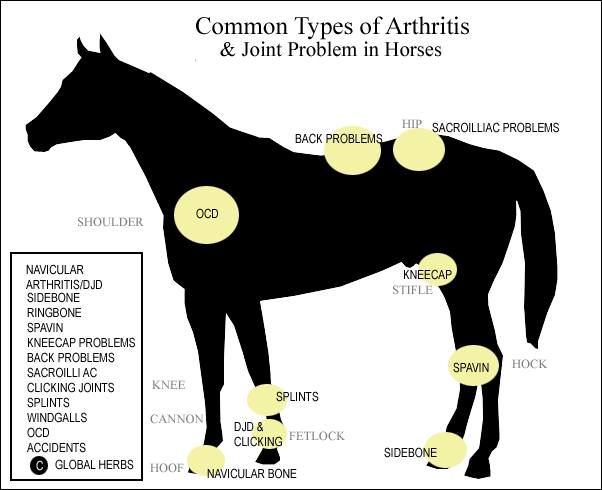

Osteoarthritis can affect any articulation, or joint. Most commonly these are limbs and include hocks, carpi, stifles, and fetlocks. Additionally, the spine, hips, and temporomandibular joint may be affected. Clinical signs include heat, pain, effusion (excess fluid in the joint), lameness, stiffness, and bone deformation. There may also be crepitus, with popping, grinding, and cracking during joint movement.

Osteophytes are small pieces of bone that form between synovium and bone, at areas of instability. Joint inflammation leads to their formation as cytokines are released that cause cells to multiply, differentiating into chondroblasts and osteoblasts. There is matrix deposition, mineralization and growth of the osteophyte. Mineralized osteophytes develop a trabecular structure and retain a cartilage surface, and when mature may become incorporated into the metaphysis itself.

Chondrocyte necrosis is initiated, degradative enzymes are released and synovitis, continued cartilage degradation and inflammation occur. There is loss of proteoglycans and lubrication in the joint. Normal joint function is altered by abnormal cartilage congruency and joint capsule anatomy. Pain, lameness and muscle atrophy develop secondary to joint dysfunction.

It is difficult to impossible to differentiate clinically, but pain can actually be classified as one of three broad ‘types,’ and each appears to contribute to the pain associated with OA.

Those three types include:

1. Nociceptive pain, which is caused by activation of pain receptors in the joint secondary to abnormal movements associated with OA.

2. Inflammatory pain, resulting from the release of inflammatory mediators that impact a variety of surrounding joint tissues. Inflammatory mediators can also “prime” the nociceptive pain receptors in joint tissues, making them more sensitive than normal and increasing pain levels.

3. Neuropathic pain, caused by damage to specific regions of the horse’s nervous system that perceive pain.

All three types of pain may need to be addressed. The exact source of pain is elusive in OA as articular cartilage is devoid of nerves, whereas ligaments, tendons, synovial membranes, and bone are all innervated.

Pain, lameness and muscle atrophy develop secondary to joint dysfunction. Degenerative joint disease is the end-stage to synovitis/arthritis, therefore early diagnosis and management is critical. Pain is gauged primarily by assessing lameness on the AAEPs scale of one to five, where five is non-weight bearing. Palpation and joint or local nerve blocks are also used to accurately determine the site of pain.

Predisposing factors to OA include repetitive or acute joint trauma, intra-articular fractures, joint instability, joint conformational abnormalities, and osteochondrosis.

Clinical signs of OA include lameness, pain, joint effusion, muscle atrophy, pericapsular fibrosis, crepitus, and decreased range of motion.

Diagnosis of OA is based upon history and clinical signs. Assuming the presence of OA without a proper veterinary examination can have serious consequences, delay appropriate treatment, and use up owner resources. There are other conditions that present with similar clinical signs. Radiographs reveal joint effusion and periarticular soft tissue swelling, osteophytosis, enthsiophytosis, subchondral bone sclerosis, and decreased joint spaces. Joint spaces are filled with cartilage that cannot be seen radiographically, but its loss causes narrowing of the joint space. Radiographic changes do not always correlate well with clinical signs, and not all degenerate joints are associated with lameness.

Nuclear scintigraphy is an excellent modality to diagnose osteoarthritis. A nuclear, or bone, scan is thousands of times more sensitive compared with radiography or x-rays. It will detect lameness much earlier than more traditional methods. Stress fractures that are not apparent radiographically will easily be detected by a bone scan. Horses with subtle, intermittent, or multi-limb lameness are ideal candidates. Sometimes the horse may block to a certain area, but radiographs and/or ultrasound examination have no abnormal findings. A nuclear scan can pinpoint the lameness as it is a physiologic representation of the affected area, but it also can give an anatomic diagnosis.

Arthrocentesis is usually unremarkable, but there may be a loss of viscosity- more watery joint fluid, rather than thick, viscous fluid. There may also be an increase in volume. A few cases may require arthroscopy for diagnosis.

Treatment is based upon rest, controlled exercise and pain relief. If obese, weight reduction is appropriate. Horses should be restricted from heavy exercise until the inflammation is controlled. Physiotherapy and hydrotherapy can be helpful. In horses, pain is generally controlled with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as phenylbutazone, flunixin meglumine, and firocoxib. Intra-articular injections with steroids and sodium hyaluronate help decrease inflammation and restore viscosity. Intramuscular glycosaminoglycans (Adequan) can be helpful to prevent cartilage degradation.

The number of overweight and obese horses mirrors the obesity epidemic in humans and other companion animals. Approximately one in three domestic horses is considered not just overweight, but obese. Every pound of extra weight results in a four pound increase in force upon the joint(s). An 11-18% reduction in body weight improves lameness and increases life span. To achieve weight loss, more energy must be used than is consumed. A combination of exercise and decreased feed intake is the cornerstone of weight management.

Horses should be turned out as much as possible. Increased low-impact exercise encourages weight loss and reduces joint stiffness. Horses should be exercised, even lightly, to maintain fitness and pliable joints.

In select cases, arthroscopy can be helpful for not only diagnosis, but also treatment. It is the only way that cartilage can be visualized, and inflammatory mediators can be flushed from the joint. In other cases, arthrodesis may be necessary. Fusion of the joint stops the instability and therefore pain. The pastern and hocks are commonly fused, although sometimes the fetlock or carpus may be ankylosed. This may limit what the horse can do athletically but removes the pain completely. In the case of the lower hock joints, which only have two percent of the motion of the hock, the horse can return to full athletic ability.

Alternative therapies, including neutraceuticals, chiropractic therapy, and acupuncture have been studied, but there are few, if any, that support any claim of efficacy. The bioavailability of chondroitin sulphate, glucosamine is only around 2%, meaning that 98% ends up outside and behind the horse.

There is no cure for osteoarthritis, and conservative treatment is meant to slow disease progression and control pain.