paykwik al

online sportwetten

paykasa

paykwik

online sportwetten

paykasa

Bit Troubleshooting – English Edition

Click here to read the complete article

The choice of bits for English classes can be overwhelming with a seemingly infinite combination of mouthpieces and cheek designs. English bits are commonly considered to be either direct rein or snaffle bits. However, some have shanks, use leverage, and are regarded as curb bits. Add in a variety of materials for the mouthpiece that range from rubber to leather to copper and it’s enough to make anyone’s head spin. However, this infinite variety has an upside: there is certainly a bit out there that will make your horse comfortable, while giving you the control and confidence you need to win.

Nancy Sue Ryan approaches bitting from the school of thought that you can get a horse to be lighter and softer in a bigger bit. “I always ride with fat snaffles,” she says. “It’s how I was taught.” She reasons, “It’s like pulling on a piano wire, versus pulling on a hose. If you have a piano wire, you’re not going to pull on it very long.” She contends that a horse is going to get off the bridle when there is a skinny bit. She continues, “To be able to teach a horse to get onto the bridle, and respect it, and be soft in the mouth, you want to use a fatter bit.”

She explains the mechanics. “You get a horse lighter in a fat bit, because they’re going to lean against it. Then, you can soften them. When you have a twisted wire snaffle, they’re going to get off the bit and get behind it. They will do whatever they can to hide from it.” She also reminds that a rider’s hands control the severity of any bit. “You can pull all day long and not hurt them. They will learn to soften. You damage your horse’s mouth when you jerk on your reins. When you have slack and snatch that up, that’s what is painful to the horse.”

She lists her go-to bits and when she uses them, saying, “I like slip rings, especially for schooling. When you take a hold of it, it will slip, and that tells the horse that you’re coming in to make an adjustment.” Her favorite slip ring has a copper mouthpiece with “a big old, slow twist.” She’s found that combination to be so successful that she has used the style and completely worn out three of them over the years.

“I love copper mouthpieces,” she adds. “It makes a horse really soft in the mouth.” As a horse’s job refines, so do her bit choices. “I ride some horses in an eggbutt or a D-ring snaffle. If they’re a little harder to guide, I might go to a full cheek snaffle. You can keep them going straighter between the reins with a full cheek, especially when you put a Non-Pro rider on them.”

Nancy Sue isn’t a fan of leveraged English bits. “The old school Kimberwick bit was a schooling bit, not a show bridle.” She says that sometimes you may see a novice rider using a D-ring with a curb chain, and she acknowledges that it may be easier for them. However, it may not have the desired effect on the horse. She says, “The horse is going on a looser rein and that’s not appropriate. In Hunter Under Saddle, we need contact. We don’t want rein drape. I think, as a novice progresses, they need to move up to a snaffle.”

Over Fence classes require yet another approach to bits. Some jumpers are shown in a two-rein Pelham for greater control. Nancy Sue shares her view on this from a judge’s perspective. “If I have two horses that have equal jumping rounds, I’m going to go with the horse in a snaffle over a horse in a Pelham. It’s a tiebreaker for me. I’ll even mark on my score sheet if the horse is in a Pelham,” she says. She explains that using a Pelham in Over Fence classes signals to her that the horse is more difficult in the mouth.

Regardless of the bit being used, Nancy Sue emphasizes that it comes down to how your hands use the bit that really makes a difference in communication. She says, “I’m a big believer in asking a horse, and as soon as they release, you release back. Ask, receive, and give. Even if you have to go back in, what they learn is that I’m not going to pull on them if they stay there.”

Lainie DeBoer is another trainer who advocates for the less is more approach when it comes to English bits. She says, “If you’re having trouble and feel like you have to go to a bigger bit, you have to ask yourself some other questions. What’s going on with this horse’s training? Where is my riding level? Am I riding them correctly? If you are just upping the bit level, I feel like you’re skipping some process. Before we ever proceed on increasing the bit, we look at the whole picture and then we slowly add to find the sweet spot.”

She starts her horses in big, fat snaffles with a loose ring or a mild French link, which has a small, flat plate between the two bars of the mouthpiece. She elaborates, “If their caps are coming in, or they’re a little funny-mouthed, we will use a D-ring leather bit. It’s called the pacifier. It’s pretty much my favorite bit of all.”

Once a horse gets older, Lainie uses a rubber gag while training at home. “It keeps the horses light and keeps their head up,” she says. The cheek pieces on a gag slide through the holes in the bit rings, which moves the mouthpiece upwards against the corners of the mouth and lips, encouraging the horse to lift his head. She describes one of her favorites. “It has a gummy rubber mouthpiece, which is great. When you pull back, it also puts a little leverage on their poll so that their head rises.”

Experience and discipline factor into Lainie’s bitting. “When we get into the higher levels of Equitation, we really like a rubber Pelham. I like the fact that you have a snaffle to work with. But, when you need the curb, it’s independent with the second rein. It’s a more sophisticated bridle, but I feel that in Equitation, where you want them a little rounder and up in front of you, you can pull up and really drive them into your hand. It’s an especially good bit for transitions,” she says.

Despite initially looking intimidating, she finds that non-pro riders adapt to the two reins of a Pelham rather easily. Lainie says, “After a couple rides, it’s no big deal. We make sure that the curb reining is thinner and smooth so it’s easy to adjust and you don’t feel like you have a lot in your hands. It’s really fun to use, because you start thinking about the mechanics of the mouth, the pressure that you’re applying, and why and when.” She doesn’t see any downside or negative reaction to using a Pelham. “We’ve probably won 15 World Championships in Hunt Seat Equitation with a Pelham.” However, she does concede, “You probably wouldn’t see a horse going into a Working Hunter class with a Pelham without thinking that maybe he’s a little heavy. But in Equitation, I feel it’s way more accepted because there is so much more adjusting, transitions, and tricky tracking work.”

She also evaluates how a horse and rider work as a team when choosing bits. “In Over Fence classes, we need our horses to pull. The horse sometimes needs to be able to bail out an Amateur rider. So, we tend to go with a pretty mild bit. I never use a really strong bit with a Non-Pro rider. You truly can cause an accident if a horse is afraid of his mouth, or is too light, or too behind the bridle.” She knows that not every jump is perfect, so it’s vital for the horse to have confidence that he’s not going to get hurt if the rider makes a little mistake in the air. “A lot can happen when you’re hurling 1,200 pounds through the air,” she laughs. “You have to make it as safe as possible.”

Lainie first evaluates potential physical causes when she has a horse that’s spitting the bit out, twisting its head, bracing, or has a look of discomfort in his eyes. She says, “If you feel like your horse has a hard mouth, look at the bigger picture. Check their teeth, get a good dentist, and get a chiropractor. Find out if there are other things going on.” Once physical triggers are eliminated, she will explore if the behavior is driven by the bit. “If I have a horse that’s fickle about bits, and I can’t quite figure it out, sometimes I will turn to a copper mouthpiece. I have a horse right now that’s a little funny mouthed. We have tried a lot on him, and I can’t figure what it is that he doesn’t like. Now, I actually wrap his bit in a latex. It’s a little outside the box; but, for some reason, he loves it.”

Lainie also uses different bits for horses that go indoors versus outdoors. She says, “We show outside in big rings or big fields, and sometimes in those situations you need a little more bit. But then, you go indoors where it’s a smaller space. It’s real bright and a little spooky. We might need to back off and go with a little less bit there.”

Lainie hates to hear people say that a horse is hard-mouthed or belligerent. “They really aren’t naturally that way. There is something in their environment that’s bothering that horse. It may be a soundness issue or teeth. So, rule out all of the things that you can control before you start amping up the bit. That’s when you will start getting behavioral problems. I’d rather have a happy horse. A happy horse will do anything for you.”

Scott Jones moves a horse into a rubber snaffle early in the training process so that he can determine what the horse’s mouth is going to be like and how the horse is going to respond to the bit. “I try to stay in that rubber snaffle for a while and then make a decision about whether I move to a smooth snaffle. If they are a little bit more harder-faced, I need to teach them to give to my hands more, so I’ll use a fat twist.”

The bit is an important part of how Jones builds a foundation on horses. “Anyone who has ever taught me about starting colts has instilled that once you get them steering and guiding, you really need to go after body control first. You add their face later as you go along. Otherwise, if you take their face away first, you won’t have control of where their body is going,” he says. His progress on body control determines if he needs to stay where he is with a bit or go to something smaller. He says, “Usually, your gut tells you what you should step to next.”

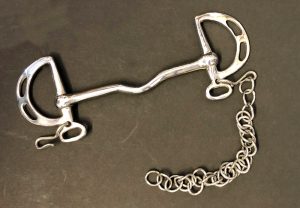

For example, all-around horses have to learn when it is appropriate to go forward and when they need a lot of collection. Scott says, “There is certainly a period of learning the difference between having two hands on a snaffle, versus one hand on a curbed bridle.” Bit choices can help with that transition. He adds, “Sometimes, all-around horses have an easier time moving from a D-ring snaffle to a D-ring with a curb chain [a Kimberwick] because it’s more familiar to them. The added leverage is a minor thing at that point.”

Jones advises that you look at the whole picture and not just zero in on the bit when troubleshooting behaviors. Things like chomping or tongue rolling can be a sign of something other than bit discomfort. “Occasionally, that’s a sign of anxiety that’s related to something else. We had one mare that did Hunter Under Saddle and Equitation. She would get to a cone and instantly pull her nose back to her chest. It took a while to figure out that it was anxiety driven from the intensity of practice for Equitation. We had to spend a lot of time so she could learn to relax and understand the difference between those two jobs.” Jumping straight to a bit change in that situation would have made the anxiety worse.

Scott has some reliable bits he uses when showing. “One of my favorite bits is a three-piece dog bone. I have actually won a lot in it. The flat piece in the middle is copper.” He has found copper mouthpieces can help with a lot of horses.

He’s a big advocate of practicing at home with the bit you intend to use at the show. “That’s usually where people go wrong. You want to figure out what bit works at home rather than waiting until you come out of the class and say, ‘Well, I didn’t like that too much!’”

Chuck Briggs specializes in Over Fence classes where full connection is important for a clean and graceful round. Yet, he’s adamant that his horses are all-around English horses that have great fluidity and movement on the flat as well. For flat work or flying, he has a straightforward approach to bitting. He says, “I start out with less rather than more, because some horses react better to ‘less’ and they tend to fight the ‘more.’ Sometimes, you get to a point where you feel like nothing is working. That’s when you have to be willing to try everything. Horses are individuals, and you can’t make one fit the mold.”

Chuck will match the bit to the rider, just as he matches the horse to the class. For instance, he will use a full cheek piece when a less experienced rider is on a horse that needs more steering control. When he shows a horse with one bit in open division, he will switch to something different when a Non-Pro is on that horse. He says, “I sometimes give an Amateur a little more bit to show with because they’re going to be less effective than a pro. If you go with less, they might get themselves in a little bit of trouble.” Yet, he’s careful not to make it a radical bit change. For instance, he says, “I’ll show in open with a twisted wire snaffle and the Non-Pro might need something with a curb chain. I’ll use a smooth mouthpiece with that curb chain. That way we are not making a drastic difference.” He makes sure his Amateurs practice at home in the show bit, however there can be too much of a good thing. “If I find that something works really well for the horse, I don’t practice with it a lot. I don’t want them to get too used to it,” he says.

The unique demands of going over fences shape Chuck’s choices for his Non-Pros. He explains, “I try not to use a curb chain on Hunters unless it’s one that pulls a lot. If they have a heavy mouth, they can tolerate a little bit of hitting them in the mouth when Jumping. But, if they have a sensitive mouth, they are only going to take it so much.”

He sees that some vices, such as chomping or tongue rolling, are directly related to the bit. “With some horses, you put a different mouthpiece in, and they just hate it. You never know what they’re going to like or not.” Sometimes, changing out the mouthpiece resolves the issue, though there is no set formula. He reiterates, “They are individuals. You have to be willing to try everything.”

English Bit Basics:

D-Ring: The D-ring snaffle has fixed cheek pieces that prevent the mouthpiece from sliding through the horse’s mouth or pinching the lips. It’s a good, basic cheek piece for starting a new or green horse.

EggButt: Eggbutts are fixed rings similar to D-rings but oval shaped. Without as much metal on the sides, they are slightly more likely to move sideways in the horse’s mouth.

Loose Ring: Loose rings are not fixed like D-rings and Eggbutts but can move freely through holes in the mouthpiece.

Full-Cheek: Full-cheeks have a smaller “D” but incorporate cheek pieces that project above and below the rings to keep the mouthpiece from sliding in the horse’s mouth. That extra structure also helps emphasize the turning aids.

Kimberwick: A Kimberwick is a leveraged bit that looks like a D-Ring snaffle with a curb chain. There are slots in the D for the reins, and the choice of position can provide more or less leverage.

Pelham: A Pelham bit combines elements of both a snaffle and a curb bit into one mouthpiece. They can have short or long shanks. The ‘Snaffle reins’ attach to a ring on the side and apply direct pressure. A second set of ‘Curb reins’, or a connecting strap, attaches to the shank for leveraged action.

AQHA ENGLISH BIT RULES:

Please consult your breed or organization’s rulebook for specific rules.

PERMITTED

• English snaffle (no shank), Kimberwick or Pelham

• Mouthpieces may be smooth, round, oval or egg-shaped, slow twist, corkscrew, single twisted wire, or double twisted wire.

• Solid and broken mouthpieces must be between 5/16” to 3/4” (8 mm to 20 mm) in diameter, measured 1” (25 mm) from the cheek and may have a port no higher than 1 1/2” (40 mm).

• Nothing may protrude below the mouthpiece (bar)

• Connecting rings on broken mouthpieces must be 1 1/4” or less in diameter or have a connecting flat bar of 3/8” to 3/4” measured top to bottom with a maximum length of 2”, which lies flat in the horse’s mouth.

• If a curb bit is used, the curb chain must be at least 1/2” in width and lie flat against the jaw of the horse.

PROHIBITED

Cathedrals, donuts, prongs, edges or rough, sharp material, square stock, metal wrapped, or polo bits.